Body neutrality and the never-ending struggle to love yourself

- Karla Cloete

- Feb 17, 2022

- 8 min read

Updated: Aug 24, 2022

By Karla Cloete

Edited by Tasmiyah Randeree & Randy Tsubane

Some celebrities feel a new movement called ‘body neutrality’ could be a better answer than ‘body positivity' to women’s self-worth struggles. But why do we hate our bodies in the first place?

You probably don’t like your body. At some point in your life, you’ve probably hated the way you look or still do. It’s not an accident; it’s very intentional and unfortunately very normal.

A recent survey found that 40% of 7 to 10-year-olds were embarrassed by their bodies, with that number shooting up to 78% in girls ages 17 to 21. It’s not just women anymore. A study in the UK found that rates of body dysmorphia are skyrocketing among young men, especially those who are avid gym fanatics.

Body positive men’s campaign. Sourced from this ad campaign.

Dr Carloine Heldman found, in her 10 years of research, that women had internalised the male gaze so much that they often viewed themselves from the third person perspective in what she calls “self-objectification”. This led to higher rates of depression, eating disorders, sexual dysfunction, lower grades and more competition among women.

She explains in her TedTalk:

We think about the positioning of our legs, our hair, where the light is falling, Who's looking at us? Who's not looking at us. In fact in the 5 minutes I've been giving this talk, on average the women in this audience have engaged in habitual body monitoring 10 times. That is, every 30 seconds.

Or as Margret Atwood eloquently puts it in her book, The Robber Bride:

“Even pretending you aren't catering to male fantasies is a male fantasy: pretending you're unseen, pretending you have a life of your own, that you can wash your feet and comb your hair unconscious of the ever-present watcher peering through the keyhole, peering through the keyhole in your own head, if nowhere else. You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman. You are your own voyeur.”

If you’ve experienced this kind of self-monitoring voyeurism, if you hate your body or struggle to have good self-worth, that’s not your fault. The shapewear industry was worth $4.03 billion in 2020 while the global market for weight loss products was worth $254.0 billion in 2021. The bottom line: your self-hatred is incredibly profitable. After decades of living in a system that intentionally bombarded us with unachievable standards of beauty, it isn’t surprising to any of us that we’ve internalised those messages.

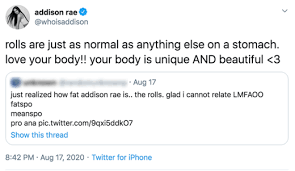

Addison Rae firing back at Twitter trolls for fat shaming (left). Zendaya responding to being called to thin (right).

Beauty standards are unrealistic and unachievable for a reason: the less you like yourself, the more willing you are to shell out on skinny tea, cellulite creams and spanx, resulting in a more profitable industry.

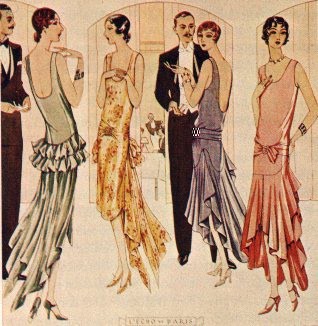

Venus or Urbino Titan showing renaissance women (left) Flapper era body ideals (right).

If you were full-bodied in Ancient Greece or had a big belly during the Italian renaissance, congratulations! You were considered beautiful. If you had a Kardashian body in the 1920s, you would have been shamed for not being thin, while the boyish figures that were celebrated in the 20s would be bullied now for not having enough curves. Even today, what’s beautiful is different from country to country.

In the West African nation of Mauritania, girls as young as eight or nine are force-fed 16,000 calories a day to make them gain weight and be considered attractive enough for marriage. While in South Korea, the plus-size K-pop group “Piggy Dolls” were ruthlessly shamed for their weight; when they reunited after losing a collective 100 pounds, they were hated for not staying true to their body positive message.

(Left) The original K-girl group Piggy Dolls. (Right) Young girl being force-fed in Mauritania.

There is nothing wrong with you and your body, no matter what shape it is. You are simply being held to ever-changing standards for corporate profit. If history has taught us anything, it’s that no matter what your body looks like, someone somewhere at some point in time will say your body is the ‘wrong’ shape.

As if corporations were not enough to deal with, there is also the toxic impact of diet culture and social media filter-rama. At this point, we all know that Instagram is bad for our mental health and body image perceptions, and that is where the body positive movement comes in.

The ‘fat acceptance’ movement was created in the 60s in the US to increase acceptance of larger bodies as well as “fat, black, queer and disabled bodies”, as Kronegold, the associate director of communications at the National Eating Disorders Association, explains. This movement was created to broaden the definition of what beauty means beyond ‘thin and white’, an important goal.

In the early 2000s, when skinny culture prevailed, eating disorders and depression among young people skyrocketed. The body positive movement has since pressured huge corporations into catering to and representing more diverse bodies. When the phrase ‘body positive’ was coined, it quickly spread across social media with hashtags like #bodylove, #allbodiesarebeautiful, #bodypositivity, #allbodiesarecreatedequal, #loveyourbody”.

Body positive ad by Lane Bryant.

Singer Lizzo has been body-shamed and trolled online more than most. She has always stood for more inclusive media representation but recently noted that body positivity has become about “celebrating medium and small girls and people who occasionally get rolls”.

“Fat people are still getting the short end of this movement,” she said. “We’re still getting talked about, memed, shamed,” she added, but “no one cares anymore”.

And she’s not wrong. While the body-positive movement created a really important change in media representation and the larger conversation about weight and self-worth, corporations and influencers have latched on and twisted it for their own gain.

Now, the movement has been “commercialised” and “commandeered by smaller-bodied influencers,” Meredith Nisbet, a supervisor at the Eating Recovery Centre, said in an interview. “Body positivity means very different things if you live in a larger body that has a lot of stigmas associated with it and if you live in a smaller body that doesn’t have a lot of stigmas associated with it,” she said.

A new movement has sprung up in response, called body neutrality. According to Kronegold, body neutrality can be more useful for most:

Singer Lizzo via ELLE.

The body positive movement urges people to love their bodies no matter what they look like, whereas body neutrality focuses on what your body can do for you rather than what it actually looks like.

“I am grateful for my legs because they got me from point A to point B, or I’m grateful for my arms because they allow me to hug my loved one,” Kronengold explained, showing how body neutrality emphasises the body’s function above appearance.

This isn’t to say that body neutrality is perfect: if you aren’t able-bodied and you deal with chronic illness, for example, you may not have the ability to celebrate the things your body can do as your pain or disability can limit that.

Infographic courtesy of BeyondBeautifulBook.

Body neutrality has been found useful in helping individuals recover from eating disorders. “The idea [is] that we can still care for our bodies even if we don’t regard them positively,” says Nisbet.

Body neutrality can also be used by athletes to encourage recovery, as body neutrality advocates for listening to the body or can be a part of practising intuitive eating.

Body neutrality has gained some huge traction. A foremost advocate is ‘The Good Place’ actress Jameela Jamill, who, after recovering from an eating disorder and a continuing struggle with body dysmorphia, found that neutrality was the only way she could cope.

"I can’t do body positivity because it still takes up too much of my time! Stand here in front of a mirror and be like, ‘I love thighs! I love my cellulite!’ I’m still too body dysmorphic to be able to do that, so instead, I just don’t talk about it. I’m neutral! I don’t love my body, I don’t hate my body," Jamill said in an interview.

"I don’t think about my body ever […] Imagine just not thinking about your body. You’re not hating it. You’re not loving it. You’re just a floating head. I’m a floating head wandering through the world."

As Jameela pointed out: Body positivity can be a lot of pressure. When you see 17 Instagram posts a day yelling about how much you should love your thighs it can be overwhelming when you aren’t in that space yet. You feel guilty on days when you don’t feel good about yourself in a cycle of toxic positivity. For most people singing odes of praise to their stretch marks just isn’t realistic and most people just don’t love their bodies every day. Body positivity leaves a lot of room open for obsessing over what we look like- while neutrality asks why we are wasting so much time thinking about it at all.

Actress Jameela Jamil via Stylist.

Body neutrality offers a new more accessible and sustainable mindset- acceptance of the body. Body neutrality isn’t trying to create new definitions of what beauty means it’s rejecting the need for those definitions entirely.

Instead of widening the circle of who can be considered beautiful, body neutrality rejects the idea of beauty being a measure of worth. The body isn’t measured in kilos or inches but in how it carries us through our lives and the importance of who we are as people.

Neutrality towards the body extends to everything- even in taking care of it. “I don’t have to be happy with my body, I don’t have to love my body, but I can still acknowledge that this is the one body that I have … and so I need to be caring for that,” Nisbet says.

Instead of thinking “I need to go to the gym to get a flat stomach,” body neutrality would say “Going to the gym helps me feel strong.” Instead of saying, “I should eat healthy so I don’t get fat,” body neutrality would say “Eating healthy gives me more energy to get through my day.”

Body neutrality is all about what your body can do, rather than what you look like in a crop top.

The hard truth is that your body isn't good enough. It will never be good enough. That isn't a cruel taunt, but it's a reflection of a larger truth: As long as you are trying to measure the worth of the body you were born in, you will always fall short, because the standards will never stop changing and the world will never agree on what’s beautiful.

I might have flabby arms, but who cares if I give really good hugs?

I have thick thighs covered in stretch marks, but why worry about that when they help me hike up mountains with my friends?

Your body isn't here to meet some standard. As long as your question is, 'Is my body good enough?' the answer will be no, not because there's anything wrong with you, but because you've been wrongly taught to ask such a question in the first place.

Infographic via Living better lives.

This isn’t to say that body neutrality is better than body positivity. They’re both important and can be beneficial to different people with very different needs in different stages of their journey. Regardless of what kind of self-love you practise, you need to know that you will never have a different body. In your lifetime, your body will change and you will change with it. Weight alone cannot serve as a measure of health nor should it be used as a metric for happiness.

You have one body and one lifetime to enjoy and care for. You can either spend all your time and energy hating and changing yourself or find a way to accept the body you were born in instead of fighting it.

“The most beautiful part of your body is where it’s headed.” - Ocean Vuong.

If you’re interested in learning more about body neutrality, Jameela Jamil designed a free course here. For concerns about mental health or eating disorders contact SADAG.

Comments